The Digital Silk Road in Suitcases: How Chinese AI Companies Are Circumventing U.S. Export Controls

A new front in the U.S.-China tech war has emerged, with Chinese engineers literally carrying petabytes of data across borders to train AI models on restricted American chips

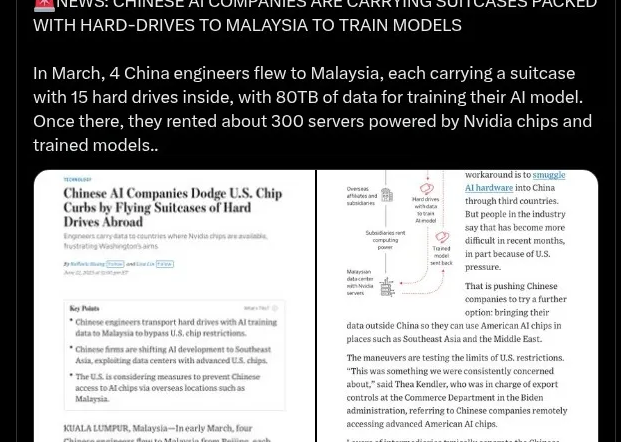

In March 2025, four Chinese engineers departed Beijing's Capital International Airport on what appeared to be a routine business trip to Malaysia. Each carried a standard suitcase, but inside lay something far from ordinary: 15 high-capacity hard drives containing 80 terabytes of data—spreadsheets, images, video clips, and other materials crucial for training cutting-edge artificial intelligence models. Together, these unassuming suitcases held 4.8 petabytes of information, enough raw data to train several large language models rivaling ChatGPT.

This wasn't industrial espionage or a dramatic heist. It was the new reality of doing AI business in an era of escalating U.S.-China technological competition, where the most valuable commodity isn't gold or oil, but access to the advanced semiconductors that power artificial intelligence.

The Great Circumvention

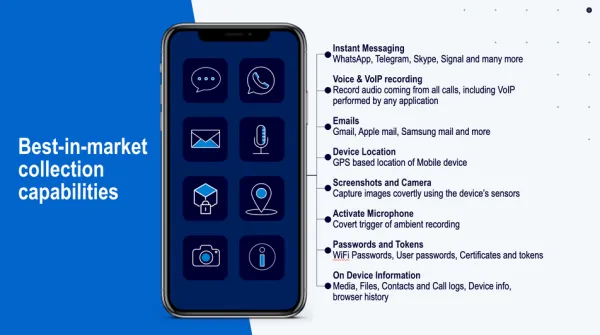

Upon arrival in Kuala Lumpur, the engineers proceeded to a Malaysian data center where their company had rented approximately 300 servers equipped with Nvidia's advanced AI chips. Over the following weeks, they used these restricted semiconductors—the same ones banned from export to China—to process their data and train sophisticated AI models. Once training was complete, they returned to China with several hundred gigabytes of model parameters, the algorithmic "DNA" that guides AI system outputs.

This elaborate workaround represents a new chapter in Chinese companies' efforts to access American AI technology despite increasingly stringent export controls. Since October 2022, the United States has devoted significant resources to restricting China's access to artificial intelligence and advanced semiconductor technologies. The strategy aims not just to slow China's immediate progress but to systematically degrade its AI capabilities over the long term.

Yet Chinese firms have proven remarkably adaptive. In May 2024, Chinese AI company DeepSeek released a best-in-class open-weight model reportedly trained on Nvidia A100 chips stockpiled before the October 2022 controls went into effect. The even more impressive Deepseek-R1 reasoning model was trained on Nvidia H800 chips, which were not restricted before October 2023. The performance of DeepSeek-R1 was so impressive that it triggered a 3.1 percent drop in the tech-heavy Nasdaq as investors questioned American AI supremacy.

From Hardware Smuggling to Data Export

The Malaysian operation required months of meticulous planning. Engineers in China spent over eight weeks optimizing datasets and adjusting AI training programs, knowing that major modifications would be nearly impossible once the data left the country. They chose to physically transport hard drives rather than transfer data online, which could have taken months and risked attracting regulatory scrutiny.

To avoid raising suspicions at Malaysian customs, the Chinese engineers distributed the hard drives across four different suitcases—a change from the previous year when they had bundled everything into a single piece of luggage. This evolution in methodology reflects the increasingly sophisticated cat-and-mouse game between Chinese firms and international enforcement agencies.

The operational complexity reveals both the value of these workarounds and their limitations. Setting up local operations and manually transporting data on hard drives makes AI training far more complicated than conducting it domestically in China. Yet as direct hardware smuggling becomes more difficult, Chinese companies are adapting by exporting their most valuable asset—data—instead of importing restricted chips.

The Geopolitical Chess Game

The Chinese company initially operated through a Singaporean subsidiary, but as Singapore clamped down on AI technology exports, the Malaysian data center requested that clients register locally to avoid scrutiny. This led to the creation of a Malaysian legal entity with three Malaysian citizens as directors and an offshore holding company as its parent—a corporate structure designed to obscure Chinese ownership while maintaining operational control.

These maneuvers highlight the fundamental challenge facing U.S. export controls. As one official told Reuters after the October 2022 controls took effect: "We recognize that the unilateral controls that we are putting in place will lose effectiveness over time if other countries don't join us." Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo reinforced this sentiment more forcefully, saying: "When I set the rules, I have to make damn sure China can't just buy this stuff from Japan or Korea or the Europeans."

The semiconductor supply chain's global nature compounds enforcement difficulties. Consulting firm Accenture estimates that inputs to a typical semiconductor chip "could cross international borders approximately 70 or more times before finally making it to the end customer." This complexity creates numerous opportunities for diversion and makes comprehensive control nearly impossible without unprecedented international coordination.

Southeast Asia: The New Battleground

Southeast Asia has emerged as a critical hub for these circumvention activities, with data centers rapidly expanding across the region. Jones Lang LaSalle estimates nearly 2,000 megawatts of data-center capacity in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia—matching Europe's largest markets.

Malaysia's position as a neutral AI hub has attracted enormous investment and suspicion in equal measure. The country's AI chip imports from Taiwan surged to $3.4 billion in March and April 2025, exceeding its entire 2024 total. Major technology companies have announced over $70 billion in Southeast Asian investments in recent months, with Malaysia particularly benefiting from pledges of $6 billion from Amazon Web Services, $4.3 billion from Nvidia, $2.2 billion from Microsoft, and $2 billion from Google.

This investment boom creates a complex dynamic for regional governments. Malaysia must "perform a balancing act" between welcoming Chinese investments and avoiding U.S. sanctions if it wants to be the region's AI hub. Malaysian officials face increasing pressure to uphold supply chain integrity while benefiting from Chinese technology investments, including Huawei's role in building the country's second 5G network.

The Enforcement Challenge

Former Commerce Department official Thea Kendler, who oversaw export controls under the Biden administration, acknowledged this was "something we were consistently concerned about"—Chinese companies remotely accessing advanced American AI chips. The complex web of intermediaries typically separating Chinese users from U.S. chip manufacturers makes it difficult to determine whether regulations are being violated.

The Bureau of Industry and Security's budget constraints severely limit enforcement capabilities. BIS carried out only about 1,000 end-use checks in 2021, with just one-tenth being pre-license verifications and nine-tenths post-shipment checks. Based on statistical modeling, to achieve 90 percent confidence that large-scale smuggling (≥10,000 chips) hadn't occurred within any six-month period, BIS would need to inspect one in every 2,000 chips globally—requiring approximately 500 inspections annually for the current global supply.

BIS's core budget for export control administration and enforcement has increased only slightly (~2.5 percent) since 2020 after accounting for inflation, despite considerable expansion of enforcement responsibilities. This resource constraint becomes particularly acute as controlled technologies proliferate and evasion techniques grow more sophisticated.

A Global Network of Circumvention

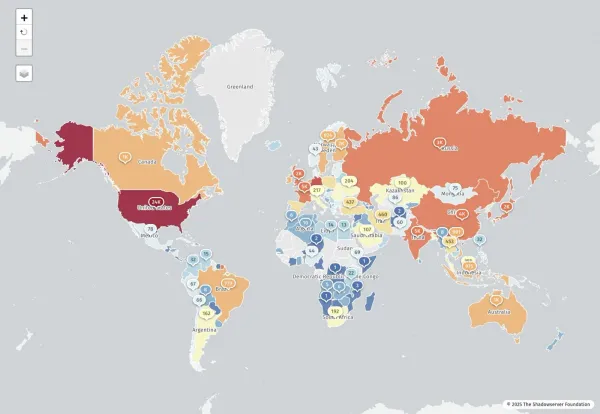

The Malaysian hard drive operation represents just one node in a broader network of circumvention activities. Organized AI chip smuggling to China has been tracked from countries including Malaysia, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates. Singapore now accounts for 22 percent of Nvidia's revenue, up from 9 percent two years ago—a suspicious surge that has attracted congressional attention.

Previous smuggling techniques have reportedly included concealing chips in live lobster shipments and using fake pregnancy bumps to transport electronics. The creativity of these methods underscores both the high value of restricted chips and the determination of those seeking to acquire them.

The financial incentives for smuggling remain substantial. The largest administrative penalty in BIS history was $300 million, while the AI chip market in China is worth tens of billions annually with very high profit margins. This cost-benefit calculation suggests that enforcement penalties may be insufficient to deter sophisticated evasion attempts.

The Middle East Alternative

Beyond Southeast Asia, the Middle East has emerged as another destination for Chinese AI developers, with Nvidia announcing significant chip sales to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE. These nations offer Chinese companies an alternative path to advanced AI capabilities while maintaining arm's-length relationships that complicate U.S. enforcement efforts.

The geographic diversification of circumvention activities reflects a maturing ecosystem of workarounds that spans multiple continents and legal jurisdictions. Each new restriction prompts innovation in evasion techniques, creating an endless cycle of regulatory measures and countermeasures.

Policy Implications and Future Challenges

The Biden administration's final export controls, released in January 2025, attempt to address these circumvention activities by establishing global quotas on AI chip sales and restricting transfers of advanced AI model weights to all but America's closest allies. The new policy divides the world into three tiers: unrestricted exports to close allies like Britain and Japan, complete bans for adversaries like Iran and Russia, and intermediate controls for most other countries including India, Brazil, and some NATO members.

However, the effectiveness of these measures remains questionable. Chinese stockpiling efforts began immediately after U.S. intentions became clear, reducing the impact of eventual restrictions. Reuters reported massive Chinese acquisition of high-bandwidth memory beginning in August 2024, months before formal controls took effect.

The action-reaction dynamic between the United States and China has created an increasingly complex regulatory environment where new restrictions prompt immediate adaptation and circumvention efforts. Each policy iteration reveals gaps that sophisticated actors quickly exploit, leading to ever-more-elaborate control mechanisms.

The Technology Cold War's New Reality

The Malaysian suitcase operation embodies the new reality of technological competition between the United States and China. Unlike previous trade disputes focused on manufactured goods, this conflict centers on controlling access to the fundamental building blocks of artificial intelligence—the chips, algorithms, and data that power the next generation of technological advancement.

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan's 2022 declaration that securing "as large a lead as possible" in force multiplier technologies like AI was a national security imperative has led to an unprecedented attempt to use export controls not just to slow China's immediate progress, but to systematically degrade its long-term AI capabilities.

Yet the Malaysian case demonstrates the limits of unilateral action in a globalized world. As Southeast Asian officials note, countries in the region face pressure to choose sides in a technological competition they didn't start but cannot avoid. The result is a complex balancing act where economic opportunities from both Chinese investment and American technology must be weighed against geopolitical pressures.

Conclusion: The Endless Game

The image of Chinese engineers carefully distributing hard drives across multiple suitcases to avoid detection speaks to both the ingenuity and desperation driving technological circumvention efforts. What began as direct hardware smuggling has evolved into data export strategies that are harder to detect and potentially more effective at scale.

As the United States and its allies continue refining export controls, Chinese companies will undoubtedly develop new workarounds. The notion that Western allies can significantly slow Chinese capabilities in microelectronics remains "a hypothesis—nothing more," as events continue to demonstrate that Chinese capacities are far from static.

The Malaysian operation may represent a new model for technological competition in an interconnected world—one where the most valuable assets can be literally carried in a suitcase, and where the boundaries between legitimate business and strategic circumvention become increasingly blurred. In this new era of technological competition, the only certainty is that both sides will continue adapting, ensuring that the cat-and-mouse game between regulators and innovators will persist for years to come.

The suitcases have landed, the data has been processed, and the models have been trained. The question now is not whether Chinese companies will find new ways to access restricted technology, but what form those workarounds will take next.