The Geopolitical Digital Fault Line: How Regulation, Quantification, and Dynamic Capabilities are Redefining Supply Chain Resilience

In a world defined by hyperconnectivity and escalating geopolitical volatility, the global supply chain has transformed from a straightforward logistical function into a core pillar of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). Cyber threats are no longer isolated IT problems; they are strategic business risks that demand board-level attention. Leaders worldwide are recognizing that defending their organizations requires a fundamental shift: moving beyond traditional cost-based procurement to adopting stringent governance, quantifying financial exposure, and building dynamic, adaptive resilience.

This article explores the confluence of accelerating cyber threats, mandatory regulatory frameworks, and the critical move toward quantifying risk that is defining the new era of Supply Chain Cyber Resilience (SCCR).

1. The Accelerated Threat: Supply Chains as the New Attack Surface

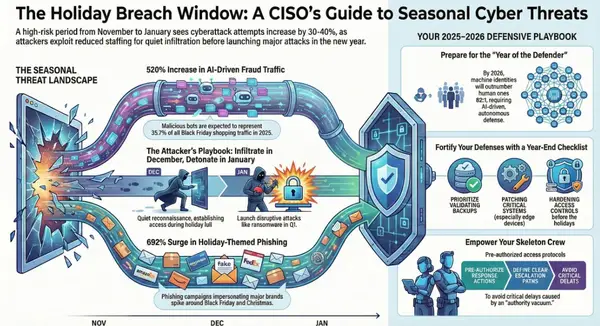

The severity of threats exploiting third-party dependencies is accelerating rapidly. Software supply chain attacks have recently been occurring at twice their long-term average. Vendor and supply chain compromise is now the number two initial attack vector for breaches and takes the longest time to identify and contain.

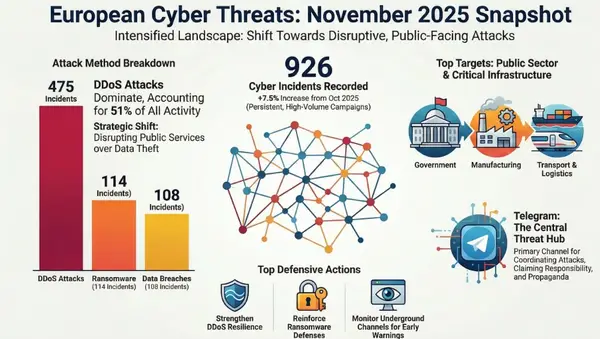

Cyber risks pose a unique and destructive triple threat to the supply chain, impacting the confidentiality, availability, and integrity of assets simultaneously. This vulnerability is acutely felt across globally critical infrastructure:

Cyber-Physical Attacks on Critical Sectors

- Maritime Transportation: The Global Maritime Transportation System, responsible for moving over 80% of global cargo, is highly vulnerable to cyber-physical system (CPS) attacks. A threat actor could compromise a ship's navigation or propulsion systems to deliberately cause a physical chokepoint disruption, echoing the operational and economic damage caused by the 2021 Suez Canal blockage, which cost billions of dollars in lost trade each day.

- Semiconductor Industry: This supply chain is widely considered the world’s most vulnerable. Adversaries utilize the complexity and opacity of supply chains to conceal their efforts to obtain intellectual property (IP) and insert malware.

- The Insider Threat: Beyond external hackers, insiders (whether malicious or negligent) pose a significant risk, leveraging trusted access to cause harm through fraud, economic espionage, or human error. Such activity is often undetected for long periods of time.

2. The Regulatory Mandate for Transparency and Resilience

Global legislative bodies are responding to these concentrated risks by mandating specific security practices and accountability measures, especially concerning ICT/OT supply chains.

The European Union's Push for Software Transparency

The European Union has introduced critical legislation that formalizes supply chain security:

- The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA): This legislation applies to manufacturers of hardware and software products featuring digital elements sold in the EU. It directly addresses supply chain risk by requiring manufacturers to identify and document components, including by drawing up a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM). The SBOM must cover, at the very least, the top-level dependencies of the product in a commonly used and machine-readable format. Non-compliance with CRA requirements is subject to fines up to 15,000,000 EUR.

- The NIS2 Directive: NIS2 mandates that entities in critical sectors (such as Energy, Transport, Banking, and Manufacturing) must implement a risk-based approach to four key areas: supply chain risk management, supplier relationship management, vulnerability handling, and quality of products and practices of suppliers. Entities must explicitly consider the security practices and overall quality of products and cybersecurity practices of their third-parties.

- DORA (Digital Operational Resilience Act): This regulation specifically enforces operational resilience and third-party risk management for entities within the financial sector.

These regulations drive compliance by enhancing transparency, ensuring accountability, and providing appropriate governance and reporting across the supply chain.

3. Quantifying Risk: Speaking the Language of the Board

Given the immense potential for financial loss—cybercrime tallied over $12.5 billion in losses in 2023—leaders are urged to transition from vague technical assessments to objective financial metrics. The World Economic Forum emphasizes that effective CISOs must quantify cyber risks and their economic impacts to align investments with core business objectives.

- Cyber Risk Quantification (CRQ) estimates the financial damage an organization could face from specific cyber exposures using real dollar terms.

- CRQ enables teams to communicate risk in financial terms that resonate with executives and support investment prioritization.

- Key quantitative models include Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR), which systematically breaks risk into components of frequency and financial impact, and the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS), which is used to score vulnerability severity to support broader risk calculations.

This need for financial protection is reflected in the massive growth of the Software Supply Chain Attack Insurance market, which was valued at $1.2 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $6.7 billion by 2033.

4. Building Dynamic Supply Chain Cyber Resilience (SCCR)

Securing the supply chain requires moving beyond traditional risk management (which addresses Acquisition, Cyber, and Enterprise Risks) to building Dynamic Capabilities (DC) that allow organizations to sense and adapt quickly to constantly evolving cyber threats. The three microfoundations of DC are essential for achieving SCCR:

I. Sensing Capabilities

Sensing involves continuously monitoring the complex digital landscape to identify threats and opportunities. This includes:

- Creating SC Cyber Risk Knowledge: Broadening awareness and understanding of cyber risks across all organizational functions, not just IT, and assessing supplier adherence through audits and third-party monitoring.

- Increasing SC Visibility: Identifying and monitoring critical SC partners and understanding information flows to address the potential for cascading effects and lateral movement beyond the first tier.

- Creating SC Cyber Threat Intelligence: Using external threat-related information to proactively determine what is planned against the SC before an attack occurs.

II. Seizing Capabilities

Seizing focuses on mobilizing resources to respond to sensed cyber threats effectively in the short term:

- Building SC Flexibility: This requires SC agility for rapid response and an updated view of redundancy. Traditional redundancy (multiple physical locations) can fail if a cyberattack impacts all locations simultaneously due to network connectivity, necessitating redundant procedures and response diversity.

- Prioritizing Short-Term Collaboration: Implementing track-and-trace processes and SC complaint management, especially when a vulnerability is discovered within a product component, to ensure swift, cross-departmental impact assessment.

- Building SC Cyber Risk Culture: Fostering a culture where staff in all departments understand that cyber risk is a holistic SC issue, supported by specialized training and simulation exercises.

III. Transforming Capabilities

Transforming involves undertaking long-term organizational and strategic reconfiguration to enhance resilience. This requires prioritizing long-term SC collaboration and enhancing cyber risk-related SC reconfiguration. This includes aligning resources, adapting contractual security requirements, and potentially replacing existing partners who fail to meet the new, heightened cyber risk tolerance.

In conclusion, the resilience of global supply chains hinges on the ability of organizations to unify security governance, financial modeling, and operational execution. By implementing comprehensive SCRM programs guided by the dynamic capabilities of sensing, seizing, and transforming, organizations can strategically navigate the digital fault lines imposed by modern geopolitical and cyber realities.