UK Government Admits Systemic Cybersecurity Failure After Years of Devastating Breaches

A rare moment of transparency reveals decades of neglect, leaving critical infrastructure vulnerable to increasingly sophisticated attacks

The Admission No One Expected

In an unusually candid moment this week, the British government did something rare in the world of cybersecurity policy: it admitted complete failure. The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology presented Parliament with a stark assessment that years of cybersecurity efforts have fallen short, warning it will be impossible to meet the ambitious 2030 target of securing all government organizations from known cyber vulnerabilities.

The Government Cyber Action Plan, unveiled Tuesday alongside a £210 million emergency investment, reads less like a policy document and more like a postmortem. "We must achieve a radical shift in approach and a step change in pace," the plan states, describing the public sector as facing "critically high" cyber risk despite years of supposed improvements.

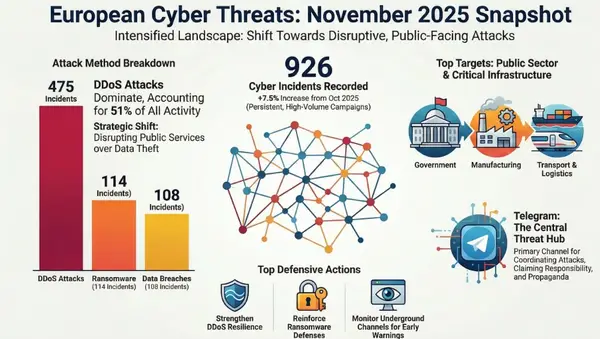

This isn't political spin or cautious bureaucratic language. This is an admission that the UK government has fundamentally failed to protect its digital infrastructure, leaving essential services vulnerable to attacks that are no longer hypothetical but "recurring realities that result in service breakdown and harm to the public." Across Europe, critical infrastructure has become the primary battlefield for state-sponsored cyber operations, with attacks on water utilities, energy grids, and democratic processes becoming routine rather than exceptional.

The cost of this failure? Lives lost, millions of records compromised, and billions in economic damage.

When Cyber Failures Kill: The Synnovis Ransomware Attack

The gravity of the UK's cybersecurity crisis crystallized on June 3, 2024, when the Qilin ransomware group struck Synnovis, a pathology services provider serving multiple NHS hospitals in southeast London. The attack didn't just disrupt IT systems—it directly contributed to a patient's death.

King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust confirmed that delays in obtaining blood test results during the cyberattack were among several contributing factors that led to a patient dying unexpectedly. A detailed patient safety investigation identified the prolonged wait for critical diagnostic information as the attack paralyzed pathology services across the region.

The numbers tell a devastating story:

- More than 10,000 appointments canceled

- 1,710 operations postponed, including nearly 200 cancer treatments

- 900,000+ patient records compromised

- £43 million in direct costs to Synnovis

- Nearly 600 patient safety incidents linked to the attack

- 400GB of sensitive patient data dumped online, including STI test results and cancer diagnoses

Synnovis didn't detect the breach immediately. The attack began and data was exfiltrated in what the company later described as a "hasty" and "random" manner from working drives. The attackers didn't access the primary laboratory database but grabbed whatever files they could during the intrusion—a detail that somehow makes the breach more disturbing. This wasn't a sophisticated, targeted operation. It was a smash-and-grab that still managed to paralyze essential healthcare services for months.

The investigation took 17 months to complete. Seventeen months before affected individuals were notified. The delay sparked fierce criticism from cybersecurity experts who noted that when vendor failures contribute to patient deaths, the clock on notification should start immediately, not nearly a year and a half later.

"The human impact, including a patient death and severe service interruptions, far surpasses the complexities of the forensic investigation," one security expert told Infosecurity Magazine. "When a vendor fails, the clock on patient safety and privacy must start immediately, not 17 months later."

The Legal Aid Agency: Four Months of Undetected Infiltration

If Synnovis demonstrated the deadly consequences of third-party vulnerabilities, the Legal Aid Agency breach exposed something potentially worse: the UK government's inability to detect intrusions into its own critical systems.

The Legal Aid Agency, which administers England and Wales' multi-billion-pound legal aid program, announced a breach on April 23, 2025. But internal investigations revealed the systems were initially compromised in December 2024—four full months before detection. Data exfiltration began in January 2025 and continued undetected until spring.

The scope is staggering. Personal data of everyone who applied for legal aid through the digital service between 2007 and May 2025—potentially over 2 million vulnerable individuals—was compromised. The stolen data included:

- Contact details and home addresses

- Dates of birth and national ID numbers

- Criminal history records

- Employment and financial data

- Debt levels, contribution amounts, and payment information

- In some cases, information about domestic violence and witness protection cases

The Law Society had warned repeatedly about the agency's "antiquated IT systems" being "too fragile to cope." In March 2024, they pointed to these legacy systems as "evidence of the long-term neglect of our justice system." The government was explicitly warned. Nothing was done.

When the breach's full extent became clear on May 16, the Legal Aid Agency took its online services completely offline. Systems remained down for months. Civil systems including the Client and Cost Management System were projected to stay offline until mid-November 2025—a seven-month recovery period that left legal aid providers unable to process cases or receive payments.

"We are not communicating everything being done to restore the system because these are the things we do not want to communicate to the outside world, to the cyber attackers," the LAA's deputy chief executive told stakeholders in October. That statement encapsulates the government's defensive posture: more concerned with secrecy than with the fundamental security failures that enabled the breach.

Foreign Office Breach: The Chinese Connection

While the Legal Aid Agency struggled with its response, another breach emerged in October 2025: the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office confirmed a cyberattack widely attributed to Chinese state-sponsored threat actors.

The attack targeted vulnerabilities in Cisco equipment, with Storm 1849—the Chinese APT group behind the intrusion—exploiting weaknesses in Cisco's Adaptive Security Appliance family. The National Cyber Security Centre had issued warnings about these specific vulnerabilities in September, urging organizations to replace end-of-life devices due to "significant risks that ageing or obsolete hardware can pose."

The Foreign Office apparently didn't act on those warnings in time.

Trade Minister Chris Bryant claimed the government "closed the hole" quickly and that security experts were confident there was a "low risk" of any individual being affected. But this incident, combined with the Legal Aid breach and Synnovis attack, paints a picture of a government consistently failing to implement basic security controls before attacks occur.

The National Audit Office Report: A Damning Assessment

The true scale of the UK government's cybersecurity failures came into focus with the National Audit Office's Government Cyber Resilience report released in January 2025. The spending watchdog's findings were brutal:

Critical Systems Assessment: GovAssure, the government's cyber assurance scheme, independently assessed 58 critical departmental IT systems by August 2024. The assessment found "significant gaps in cyber resilience" with "multiple fundamental system controls at low levels of maturity" across departments. These included deficiencies in:

- Asset management

- Protective monitoring

- Response planning

Nearly a third (28%) of assessed systems were rated "red"—meaning high likelihood and impact of operational and security risks.

The Legacy IT Crisis: As of March 2024, government departments were running at least 228 legacy IT systems. These are systems that are:

- End-of-life products with no vendor support

- Impossible to update with modern security patches

- No longer cost-effective

- Above acceptable risk thresholds

The government doesn't know how vulnerable these 228 systems are to cyberattack. It's running critical infrastructure on technology that can't be properly secured, and it hasn't even completed a comprehensive vulnerability assessment.

Legacy technology comprises 28% of the central government's technology estate, up from 26% in 2023. In some police forces, legacy systems account for up to 70% of IT infrastructure. The problem is getting worse, not better.

The Funding Disaster: In March 2024, departments lacked fully funded remediation plans for 53% (120 out of 228) legacy IT assets. The government is running these vulnerable systems with no clear plan or budget to fix them.

The NAO estimated that government spent nearly half of its £4.7 billion IT expenditure in 2019 just keeping legacy systems running. That's approximately £2.35 billion annually spent on maintenance rather than modernization—money that disappears into keeping aging, insecure systems barely functional.

Underinvestment in technology and cyber defenses was explicitly identified as a key factor in the British Library ransomware attack in October 2023, which has already cost £600,000 with significantly larger expenses anticipated as recovery continues.

The Skills Shortage: One in three cybersecurity roles in government was either vacant or filled by temporary staff in 2023-24. This represents the "biggest risk to building cyber resilience" according to the NAO.

Financial pressures have forced departments to significantly reduce the scope of cyber resilience programs, which will inevitably increase the severity of attacks when they happen. The government is cutting cybersecurity investment during a period when threats are escalating exponentially.

The Regulatory Two-Tier System

As the government unveiled its new action plan, Parliament was simultaneously conducting the second reading of the Cybersecurity and Resilience Bill (CSRB). The timing is not coincidental—it's an attempt to address one of the bill's most significant criticisms.

The CSRB establishes what critics call a "two-tier system" where private sector entities operating essential services face stronger, more enforceable obligations than public sector organizations providing the same services. Private companies can be fined and face regulatory sanctions. Government departments face... unclear consequences.

The European Union's comparable legislation, NIS2, doesn't feature this separation—a distinction that becomes particularly stark when examining Europe's own critical infrastructure vulnerabilities exposed during the 2025 Collins Aerospace ransomware attack that paralyzed major airports across the continent. Public and private sectors are held to the same standards under NIS2. But in the UK, the government has created a system where it holds itself to a lower standard than the companies it regulates.

Jamie MacColl, cyber research fellow at RUSI, was blunt: "I think timing of the Government Cyber Action Plan is partly designed to mitigate some of the criticism about the majority of the public sector not being in scope of the CSRB, unlike how the European Union has included the public sector under NIS2."

The action plan promises that "senior leaders in government will be held responsible for cyber outcomes." But MacColl noted there are "no meaningful enforcement mechanisms if government departments and agencies aren't meeting the standards the action plan sets out."

It's governance theater: promises of accountability without the enforcement mechanisms to make accountability real.

The New Government Cyber Action Plan: Too Little, Too Late?

The government's response centers on the new Government Cyber Unit, to be established by next year within the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. This centralized unit will:

- Set mandatory policy direction for all government organizations

- Coordinate implementation activities

- Provide a single point of accountability

- Oversee strategic supplier relationships

- Manage cross-government incident response

The approach represents a shift from nonbinding guidance to mandatory requirements—from asking nicely to attempting enforcement. But enforcement against whom? Without clear mechanisms to hold senior leaders accountable, it's unclear whether this centralization will result in actual improvements or just create another bureaucratic layer.

The £210 million investment sounds substantial until you examine the scale of the problem. The government estimates cyber attacks cost UK businesses £14.7 billion annually—0.5% of GDP. One expert noted that the Jaguar Land Rover hack alone cost 0.5% of GDP, putting the £210 million investment in stark perspective.

"£210 million sounds impressive until you remember the Jaguar Land Rover hack cost 0.5 percent of GDP," said Colette Mason, cybersecurity consultant. "That's the real benchmark here. Not whether we have a plan, but whether this plan can actually plug holes faster than an army of attackers find them."

The investment breaks down across three phases:

- Building (until April 2027): Establishing the Government Cyber Unit, creating governance structures, launching central services, and developing the new Government Cyber Profession

- Scaling (2027-2029): Expanding services and support based on identified needs

- Improving (April 2029 onwards): Leveraging data insights for evidence-based investment and sustainable service delivery

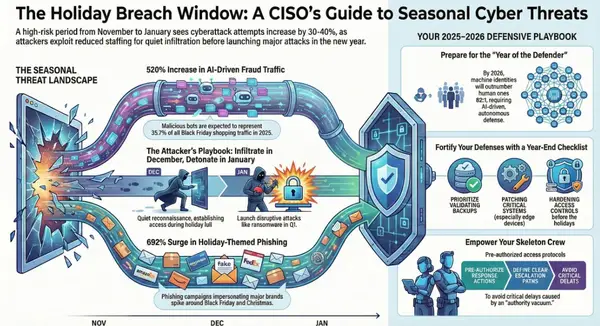

That timeline means the building phase alone takes over two years. Meanwhile, state-backed actors and ransomware groups aren't waiting. Anne Keast-Butler, head of GCHQ, warned in 2024 that the UK faced four times as many attacks as the previous year—a 400% increase in threat volume while the government plans committee meetings. Across Europe, critical infrastructure is under sustained assault from state-sponsored actors, with Russia's APT28 targeting everything from air traffic control systems to water utilities.

The Third-Party Vulnerability Problem

One of the most significant aspects of the Government Cyber Action Plan is its focus on supply chain security. Strategic suppliers to government will face "stronger contractual expectations around cyber security," reflecting the assessment that third-party vulnerabilities pose a growing threat to public services.

This is not a theoretical concern. The Synnovis attack was a third-party breach that killed a patient and cost over £40 million. The attack demonstrated how a single vendor's security failure can cascade across entire healthcare systems.

But stronger contractual expectations mean little without the government doing its own part. You can't mandate security standards for suppliers while running 228 legacy systems you haven't even assessed for vulnerabilities. The government can't credibly demand that vendors implement modern security controls while departments operate Windows servers that haven't received security updates in years.

What This Means for CISOs Globally

The UK government's public reckoning with its cybersecurity failures offers valuable lessons for security leaders everywhere—lessons that become even more urgent when viewed against the broader 2025 cybersecurity landscape marked by a 47% year-over-year increase in weekly attacks and sophisticated state-sponsored campaigns targeting critical infrastructure globally:

1. Legacy Systems Are Not Just Technical Debt—They're Security Debt 28% of the UK government's technology estate is legacy systems. These aren't minor inconveniences; they're existential risks. Every day these systems remain operational is another day of exposure to known vulnerabilities that can't be patched.

CISOs need to frame legacy system discussions in terms of security risk, not just operational efficiency. The cost of keeping old systems running isn't just maintenance—it's the eventual cost of the breach that legacy infrastructure will inevitably enable.

2. Detect or Die The Legal Aid Agency was breached for four months before detection. Four months of data exfiltration while the government remained blissfully unaware. This is unacceptable in any organization, but particularly damaging in government systems holding data on vulnerable populations.

Detection capabilities must be a top priority. You can't respond to what you don't see. Organizations need comprehensive monitoring, behavioral analysis, and threat hunting programs that can identify anomalous activity before attackers achieve their objectives.

3. Third-Party Risk Is Your Risk Synnovis proved that vendor breaches can have the same impact as direct breaches—sometimes worse. When a pathology provider gets hit by ransomware, patients die. The NHS couldn't outsource the consequences of the attack to its vendor. This pattern repeated across Europe in 2025, when a single ransomware attack on Collins Aerospace's airport check-in systems paralyzed London Heathrow, Brussels Airport, and multiple other major hubs simultaneously—demonstrating how centralized technology providers become single points of catastrophic failure.

CISOs need to approach third-party risk management with the same rigor they apply to internal systems. That means regular assessments, security requirements in contracts, incident response planning that includes vendor scenarios, and hard conversations about acceptable risk levels.

4. Transparency Is Painful But Necessary The UK government's admission of failure is remarkable because it's so rare. Most organizations—and most governments—would downplay the systemic nature of their security failures, offer vague promises of improvement, and hope the news cycle moves on.

But transparency about security posture, incidents, and organizational challenges is the only path to actual improvement. You can't fix problems you won't acknowledge exist.

5. Funding Security Requires Honest Cost-Benefit Analysis The UK government allocated £210 million to address a problem that costs the economy £14.7 billion annually. This disconnect between investment and impact is common across organizations.

Security leaders need to articulate the real cost of security failures in business terms executives understand. Not theoretical risks but actual costs: recovery expenses, regulatory fines, operational disruption, reputational damage, and in the case of healthcare, human lives.

6. Accountability Without Enforcement Is Meaningless The UK's two-tier regulatory system demonstrates what happens when you create accountability frameworks without enforcement mechanisms. Private companies face fines and sanctions for security failures. Government departments face... strongly worded internal memos?

Real accountability requires consequences. Whether through regulatory enforcement, executive compensation structures, or public disclosure requirements, there must be meaningful repercussions for security failures at the leadership level.

7. Skills Shortages Won't Fix Themselves One in three cybersecurity roles in UK government is vacant or filled by temporary staff. This isn't a problem that resolves through normal hiring practices. The shortage represents a fundamental mismatch between what security work pays in government versus private sector alternatives.

Organizations facing similar challenges need creative approaches: meaningful compensation increases, career development programs, flexible work arrangements, and collaboration with educational institutions to build talent pipelines.

The Systemic Problem: Culture, Not Just Technology

Reading through the NAO report, the Government Cyber Action Plan, and the various breach notifications, a pattern emerges. This isn't fundamentally a technology problem. It's a culture problem.

Government departments treat cybersecurity as a technical issue to be delegated to IT teams rather than a strategic risk requiring senior leadership engagement. The Government Cyber Action Plan explicitly identifies this as a problem, promising that "senior leaders in government will be held responsible for cyber outcomes rather than being allowed to treat security as a purely technical issue."

But promises aren't organizational culture. Culture change requires:

- Executives who understand security risks and make informed decisions about acceptable risk levels

- Governance structures that elevate security discussions to board-level conversations

- Funding models that adequately resource security programs

- Accountability mechanisms that create real consequences for security failures

- Transparency about security posture, incidents, and challenges

The UK government has decades of evidence that its current approach doesn't work. The 2022 Government Cyber Security Strategy set an ambitious target: all government organizations would be "significantly hardened" against cyber attacks by 2025. The NAO report makes clear this target wasn't met. The 2030 target has now been acknowledged as impossible to achieve.

The pattern is clear: set ambitious targets, create impressive-sounding strategies, allocate insufficient resources, avoid accountability when targets aren't met, repeat.

Looking Forward: Can the UK Government Actually Change?

The Government Cyber Action Plan's three-phase approach extends to 2029 and beyond. That's at least four more years before the government expects to have achieved meaningful improvements in cybersecurity across the public sector.

Four more years of running 228 legacy systems with known vulnerabilities. Four more years of third-party attacks like Synnovis. Four more years of inadequate detection capabilities enabling months-long breaches like the Legal Aid Agency. Four more years of watching as threat actors grow more sophisticated while government defenses lag further behind.

The £210 million investment is a down payment, not a solution. The NAO estimates that in 2019, government spent £2.35 billion just maintaining legacy systems. The cost of actually modernizing that infrastructure will be multiples higher.

And this assumes that funding for cybersecurity won't be cut when the next budget crisis hits, which the NAO report indicates has already happened in several departments.

The Government Cyber Unit offers the possibility of better coordination and accountability. But a centralized unit can only be effective if it has real authority, adequate resources, and political backing to force departments to prioritize security over other operational concerns. Previous attempts at centralization have foundered on departmental resistance and competing priorities.

The expansion of the CSRB to cover managed service providers, data centers, and critical suppliers is positive. But the two-tier system—where government holds itself to lower standards than private companies—undermines the credibility of the entire regulatory framework.

The Cost of Failure

The UK government's cybersecurity crisis represents a convergence of decades of underinvestment, inadequate governance, skills shortages, and a fundamental failure to treat cybersecurity as a strategic priority rather than a technical problem.

The human cost is measured in lives lost, like the patient whose death was contributed to by the Synnovis attack. The financial cost runs into billions annually. The societal cost includes eroded trust in government services and critical infrastructure.

But perhaps the most significant cost is opportunity cost. Every pound spent on maintaining antiquated systems or recovering from preventable breaches is a pound not spent on improving public services. Every hour security teams spend fighting fires created by inadequate basic controls is an hour not spent on strategic improvements.

The UK government has admitted failure. That admission is the first step toward change. But admission alone accomplishes nothing. The test is whether this moment of transparency leads to sustained investment, cultural change, meaningful accountability, and a genuine commitment to treating cybersecurity as the strategic imperative it has become.

Based on decades of evidence, there's little reason for optimism. But the alternative—continued denial, inadequate investment, and repeated high-profile breaches—has proven unsustainable.

For CISOs watching this unfold, the message is clear: the problems the UK government faces are not unique to government. Legacy systems, inadequate investment, skills shortages, third-party risk, and detection failures plague organizations across sectors and geographies.

The question isn't whether these problems exist in your organization. The question is whether you'll address them proactively or wait for your own Synnovis moment—when the theoretical risks become very real consequences, and transparency is no longer optional.

The UK Government Cyber Action Plan is available at gov.uk. The National Audit Office report on government cyber resilience provides detailed analysis of the systemic failures documented in this article. Both make for sobering reading for anyone responsible for organizational security.